There’s lots of slang in Australia and lots that I don’t understand, like ”shirt-front”.

Shirt-fronting (sporting reference): to charge at a rival and hit him so he falls to the ground, or to grab a rival by the lapels or the front of the shirt and challenge him.

I had to look it up because prime minister Tony Abbott told local press he would ”shirt-front” Russian president Vladimir Putin over Australian deaths on flight M17 at the November G20 summit in Brisbane.

Lack of diplomacy aside, it’s the combination of Abbott’s shirt-fronting whoopsie and recent racist incidents that made me want to write about the power of words.

Which brings me to the way the word team has been used by politicians.

When the prime minister discussed new counter-terrorism laws in August he said everyone who migrated to this country needed to be on team Australia. Then this morning as I stretched out after a run under the glorious purple of the Jacaranda blossoms, I came across ads for ”team Brisbane” in a local newspaper.

Now apparently team Brisbane is a marketing strategy to boost civic pride and the city’s status ahead of the G20 and after. An uninspired tourism money grab. Team Australia is a grab for what? votes? unity? a national conscience?As an immigrant I could either brush these slogans off or I could take a stand.

Two words carry a lot of power.

They make me feel like I don’t belong.

In fact, these slogans make me wonder if — even though I’m on a project to try and search out a sense of belonging here in Australia — maybe this isn’t a place where I’d like to belong.

Let me add that I’m a white migrant, educated, middle class, from a first-world country. I speak two languages of which English is my mother tongue. If “team Australia” generated such antipathy me, I wonder how immigrants and refugees from other cultures and places and backgrounds and experiences feel? What about Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders?

As a permanent resident who’s considering taking on Australian citizenship I want to point out that rhetoric like team Australia or team Brisbane serves to divide rather than unite.

Team slogans oversimplify a complex and increasingly diverse culture. They help marginalize and belittle not just migrants and refugees, but the Indigenous, the introverts, the artists, the intelligent free thinkers, and anyone else who falls outside this box whether they want to or not. They are also — to state the obvious — lacking in imagination.

Perhaps the most dangerous thing about slogans is that they encourage Groupthink.

Groupthink silences the voice of the individual, particularly anyone who disagrees, and it helps remove accountability. The group ends up making faulty decisions because they ignore alternatives and tend to take irrational actions that dehumanize others groups, according to social psychologist Irving Janis who coined the term in 1972.

Groupthink catchphrases as simple as ”team Australia” or ”unAustralian” (please do tell me what that means), reinforce an ‘us versus them’ mentality. Groupthink appeals to people who already endorse a narrow view of a society that should be just like them. Not different. Not diverse. Not complicated.

What does this mean on the streets of Australia?

It means visible minorities will be even more marginalized.

It encourages those people who feel they have the right to tell others speaking foreign languages in public places to speak English. It means some people feel they have the right to throw bottles of water at cars playing Lebanese music and verbally assault minorities.

Does that sound like something we want to encourage?

And yet, during my time in this country, I have come to admire some Australians, not for their conformity, but for what seems to be the lost art of speaking out when no one else will, for their work with the disadvantaged and the disenfranchised, for their innovation and creativity.

Australians have the possibility of drawing on many different backgrounds, languages, cultures and ways of being. Two-word slogans don’t do this.

Multiculturalism isn’t about having different foods and festivals. It’s about giving minorities a voice and accepting them not just tolerating them. It’s about respecting them enough to learn more about their cultures. Multiculturalism is about having ethnic minorities and visible minorities in positions of leadership.

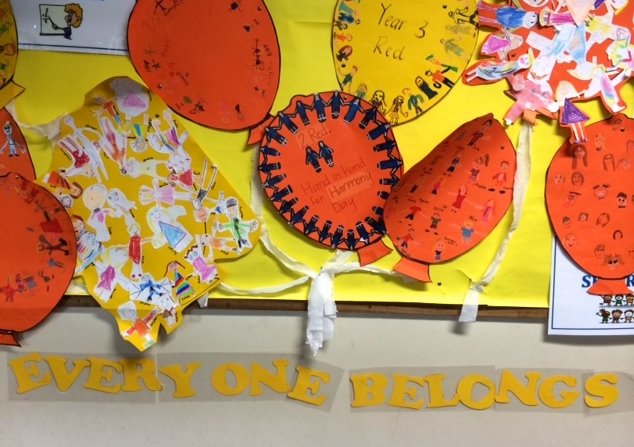

True belonging isn’t about rallying blindly behind the war cry of team Australia. It’s not about using team Brisbane as a marketing ploy.

It’s about people like me being able to question, and say, you could do so much more with the power of words.