“So what do you do?’’ the plastic surgeon asks, pulling a trolley of scalpels and scissors and suture material to the operating daybed.

“I’m a writer,’’ I say. “Actually, I just became an award-winning essayist.’’

As I talk, I wonder how I can turn this into an essay. How can I excavate this surgical experience in the same way the doctor is slicing through layers of my skin and subcutaneous fat. I stare at the ceiling, away from my right thigh. I don’t want to see blood.

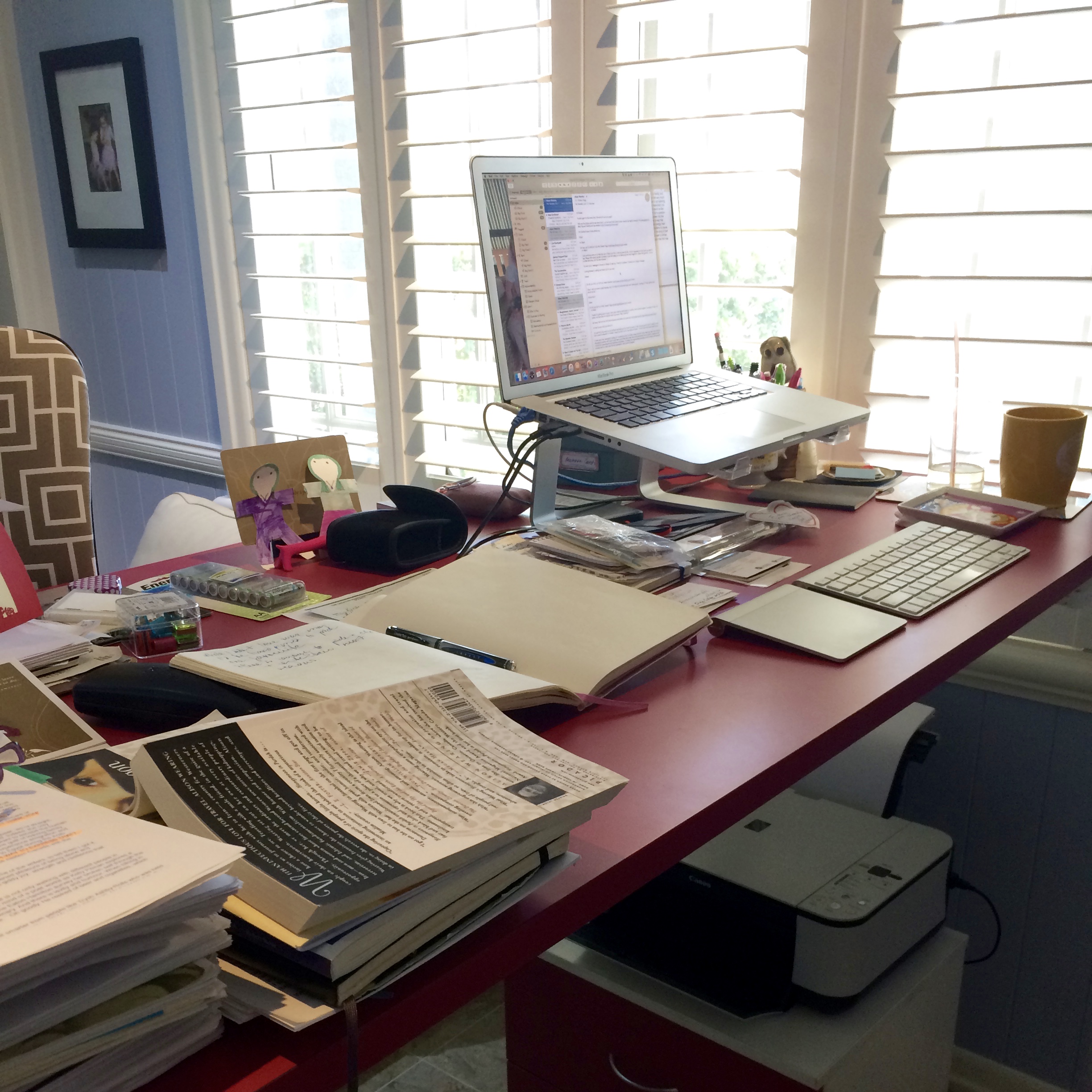

I’m writing four essays, five interviews, blogging, reading, writing book reviews and teaching creative writing to refugee kids. I have a fat moleskin of squiggles to categorize and type into the appropriate files.

The doctor pushes stitches in and out, pinches in my skin.

I need to be more organized.

“No exercise for three weeks,’’ he says. He takes off his surgeon’s glasses and I note the long slim indents on his temples just in case I need those details later.

In my mind, I transfer my exercise hours to reading and writing.

So this is the life of an award-winning essayist who is also a mother, a lover, and a friend in a world that seems to be moving too quickly.

I have notebooks and pens and pencils in the car, on the dusty shelf by the kitchen counter, on the blue stool next to the toilet, rolling around next to my daughter’s anti-fungal cream in my handbag and stuck somewhere in the piles of love clutter on the dining room table.

Every morning except Sunday I get up at five. I make chai tea and tiptoe past the girls’ bedroom. I walk around the one creaky floorboard in the front hall, downstairs to my study. I choose between breakfast and makeup, between lunch and playing my flute. I eat salmon from a tin at my desk. I decline mid-morning coffees and lunch dates.

“No, I’m sorry. I can’t go roller skating on Thursdays.’’

“What’s your excuse this time?’’ she asks.

“I’m writing.’’ I cross her off my mental list.

After I leave the girls at school I ignore phone calls from overseas friends and family. Because I am working.

Imagine. You have five hours — if you don’t count the time to clean up the kitchen, put the laundry on, sweep up the dog hair, go to the toilet, hang the laundry out. Your standards plummet. You multi-task: you pay bills online and schedule in doctors, dentists, and grade four math tuition. You transfer 3000 dollars for one term of choir lessons. You don’t notice. They phone and tell you. They reimburse your stupidity.

In between rejection letters, you write and rewrite at the library. You use words to peel back protective barriers and discover something new, to find answers to questions you hadn’t even articulated. You write amid, not despite, the turbulence of life. You search for your pen, your phone, your voice recorder when words flow in the car, breast-feeding your babies or wiping dog diarrhoea from the hoop pine floors. You memorize sentences that land on you during concerts or early morning runs and you tattoo them on the back of your hand, the delicate skin of your forearm.

“This essay is garbage,’’ you say to your writing buddy who is linked to your soul through letters and the smell of paper.

To grab more time you try online grocery shopping. If you stop waxing your legs, underarms and bikini line you could save 26 hours a year. If you get laser treatments and remove the hair permanently, you lose ten of those hours, but only once. You don’t watch TV. You have rock climbing dates in the evening with your husband. It’s good exercise and you get to talk together without interruption. You wonder if you can train yourself to be an insomniac.

“I brought you girls an after-school treat.’’ I twist around to the back seat of the car against the advice of my chiropractor and pass two peanut-butter chocolate chip cookies to grubby hands. I put on some Mozart.

“My throat! My throat! It’s burning–’’ my six-year old screams. I pull over the car. Her face is red and white.

“Spit it out! Spit it out!’’ I yell, passing her wipes. I drive to the nearest pharmacy, the one near the doctor’s office. We’ll be safe here. I’d forgotten about that peanut choking thing on the plane from Singapore to London. The pharmacist gives my youngest antihistamines and my eldest some lip balm. It will be OK. I can take her home now. I carry Aria inside to her bed, my leg throbbing from yesterday’s surgery. The builder needs to talk about the pool repairs and the piano teacher arrives. Aria throws up on her bed, spewing bile on the sheepskin rug and down the tower of toys wedged between the night-table and pink sheets. I’m vaguely aware that my eight-year old has wandered outside to question the builder about his two missing fingers.

When the babysitter arrives I’m bent over paper-toweling stringy vomit and I’m laughing. I’m not sure why I’m laughing. I go outside to the builder. I wish I could move my eyeballs separately so I can watch the builder talk and gesture and still keep an eye on Elsa as she pads in her stocking feet to the concrete swimming pool that’s being refilled with water.

Somehow I get the builder sorted, I keep Elsa dry and shuffle her inside to her piano lesson. I carry my laptop upstairs and ease myself onto the bed with an icepack on my wound. I have an hour to write.

This essay was first published on the CNFC website: http://www.creativenonfictioncollective.ca/members-blog-the-life-of-an-award-winning-writer/